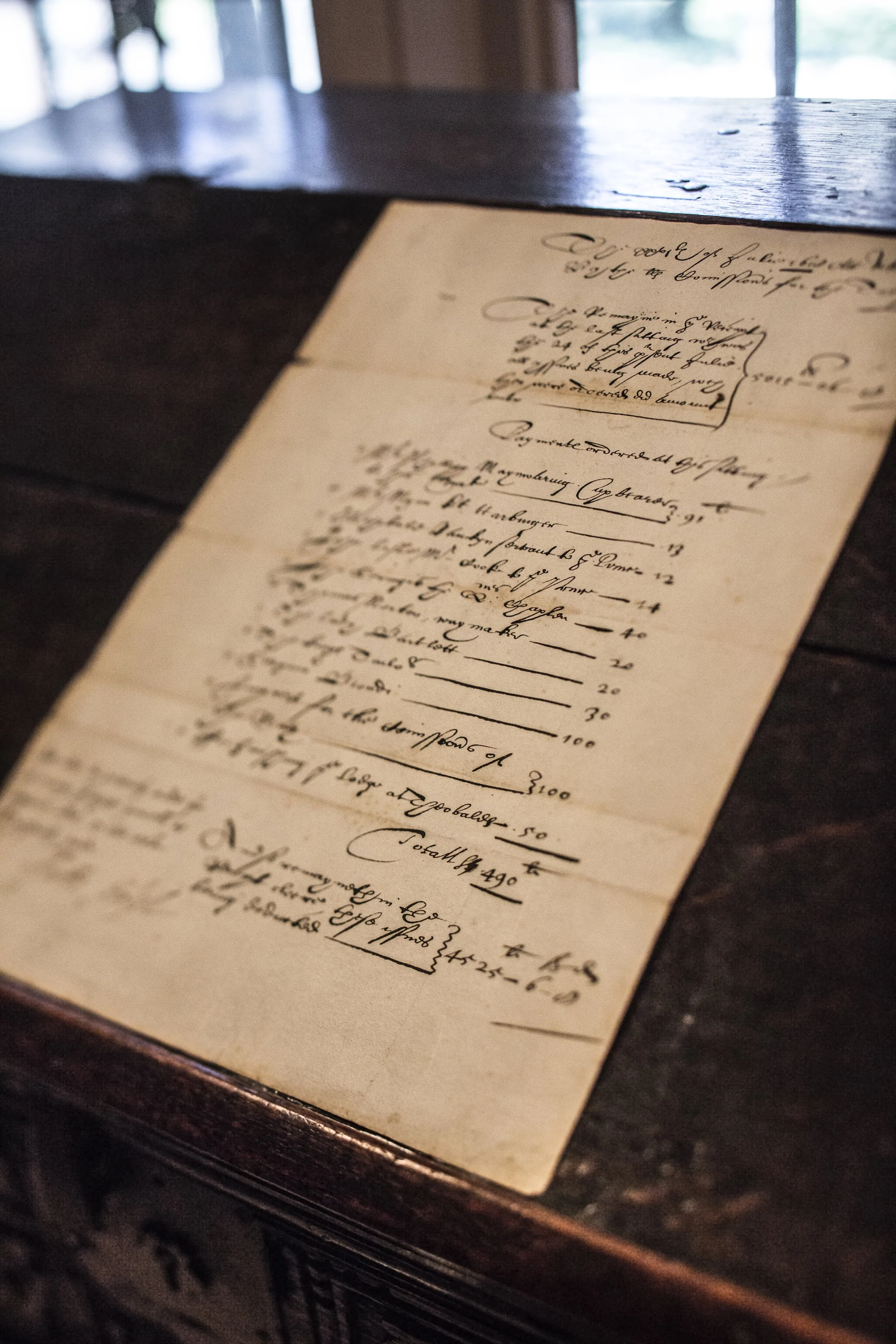

A receipt of payments disbursed at a royal sitting on 24 July 1618, signed by Fulke Greville.

[Physical Details] This manuscript was found in the Rasmussen-Hines Collection’s copy of the first edition of Greville’s Certain learned and elegant works of the Right Honorable Fulke Lord Brooke, printed by Elizabeth Purslowe for Henry Seyle in 1633.

This document offers an interesting snapshot of life in the court of King James I. In it, Fulke Greville, commissioner of the Treasury, authorized payments totaling just over £5015 for various expenditures. Greville himself, a courtier and author, is remembered for his literary work, particularly his biography of his friend Sir Philip Sidney. The recipients and projects named on the document are listed below with some conjectures as to their identities or contexts; however, much work remains to confidently identify these individuals and to situate this document within its specific moment in time. A preliminary transcription of the full manuscript is included below.[1]

“Master Phillipp Maynewering Cupbearer to his Majestie”: Philip Mainwaring, the king’s cupbearer, was twenty-nine in 1618 and surely knew that his position marked him as a man who was “going places”—the position of cupbearer had been held as recently as 1614 by George Villiers, James’s favorite, his reputed lover, and, as of 1618, the Marquess of Buckingham. With the help of his patron, the earl of Arundel, Mainwaring was later knighted and elected as a Member of Parliament; however, his Royalist views saw him arrested in 1650.

“Master Mynn Knight Harbinger”: Thomas Mynn, who served both James I and Charles I as a Knight Harbinger. The knight harbinger was sent ahead of the king’s retinue to arrange lodging when he traveled. The Cecil Papers for August 1618 reference the king’s recent trip to Cranbourne; perhaps Mynn was being paid for his services during that expedition. In 1653, years after Thomas Mynn’s death, his son John, who had been imprisoned in the Fleet, possibly as a debtor, appealed to the state for debts owed by the late Charles to his deceased father. Another suit related to his daughter Jane’s rights to the money owed to Mynn was brought in 1663.[2]

“Archibald Rankyn servant to the Prince”: As indicated, Archibald Rankin/Ranking, a Scot, served Charles, Prince of Wales. In 1629, he was appointed to the retinue of Sir Thomas Roe when Roe, as ambassador to Poland, was sent to negotiate peace between Sweden and Poland. Rankin may have been the “truly loyal hearted, learned, well accomplished Gentleman, Mr. Archibald Rankin” to whom John Taylor, the Water Poet, dedicated his 1628 jest-book, Wit and Mirth.

“John Lisle Master Cooke to the Prince”: John Lisle’s background is unknown, but he served Charles as master cook until at least 1635. The State Papers of Charles I (domestic) include an entry, dated 2 March 1634/5 about cooks’ salaries which mentions Lisle’s salary when Charles was the Prince of Wales — £9 5s 4d per year. In 1635, Lisle, still serving as the king’s master cook, asked to be given a grant of land in the next plantation of Ireland, and on 30 July 1635, King Charles granted this request. I haven’t been able to discover whether Lisle ever received the promised lands.

“John Seringis the Queens Chaplen”: Johannes Sering (d. 1631) began his service to Queen Anne upon her marriage to James—the marriage accords stipulated that the Queen be attended by a German or Danish Lutheran chaplain to support her in her Lutheran faith. The Thuringia-born Sering, who had attended Rostock University, was hired by James VI when he traveled to Denmark to meet Anne. Although Anne is rumored to have secretly converted to Catholicism, and Sering to Calvinism, Sering, known as the “Dutch chaplain,” remained in her household until 1621.

“Thomas Norton waymaker”: Thomas Norton served as a waymaker, responsible for keeping the roads in repair. Norton had previously been assigned to repair the roads from London to Royston and to Newmarket in 1609, the better to reach the lodge James had purchased in Royston and the palace he had built in Newmarket. Further details of Norton’s life are currently unknown. As in the case of Thomas Mynn, the Knight Harbinger, this may connect to the King’s trip to Cranbourne.

“The lady Bartlett”: Bradin Cormack suggests that “Bartlett” could be an alternative spelling of “Berkeley,” making the recipient of this payment Elizabeth, Lady Berkeley, daughter of George Carey, 2nd Baron Hunsdon, and his wife Elizabeth Spencer. Both mother and daughter were important patrons of the arts; it has been suggested that Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream was first performed and Elizabeth Carey’s wedding to Thomas Berkeley. Lady Berkeley was not the only “Lady Bartlett” active at the time, however. Lady Mary Bartlett (née Dauntsey) was the wife of Sir Thomas Bartlett, who served as Carver in Ordinary to Queen Anne. Bartlett attempted unsuccessfully to establish a monopoly of the London pin and wire business. Although he obtained a grant for sole right importation of pins in March 1618, the scheme eventually collapsed and, according to George Unwin, Bartlett “driven to desperation, made himself so troublesome to the Government” that he was sent to the Tower and died soon after. In July 1618, however, he likely would have still been in favor, making a gift to Lady Bartlett feasible. John Donne knew the Bartletts and even lodged with them for a time, as had his friend Sir Henry Goodere; Donne mentions both Thomas and Mary Bartlett in his letters.

“The kinges Tailor”: Unknown

“Seignior Biondi”: Likely Giovanni Francesco Biondi (1572-1644), a writer and Italian diplomat who was paid by James to spread Protestantism in Italy and served James in the negotiations of several proposed marriages for James’s children. By 1618, he was working as a double agent, reporting to the Venetians.

“Imprest for the commissioners of the Navy”: Unknown

“For finishing the lodge at Thebalds”: This entry refers to building work ordered by James on his favorite country estate, Theobalds House, in Hertfordshire. Originally built by William Cecil, Lord Burghley, to accommodate the Queen on visits, James stayed at Theobalds on several memorable occasions, including a visit from James’s brother-in-law, King Christian IV of Denmark, which descended into a drunken bacchanal. Although a masque of Solomon and Sheba had been planned, with scenery commissioned from Inigo Jones, according to Sir John Harington, the players were too drunk to remember their lines. James traded Hatfield Palace to the Cecils for Theobalds in 1607 and used it for hunting. He died there in 1625. After the execution of Charles I, Theobalds was demolished by the new Commonwealth.

Dr. Molly G. Yarn

________________________

Transcription

(Bradin Cormack)

The xxvith of Julie 1610 Att Whitehall

By the ?? llords?? Commissioners for the Treasurer

The Remaine in the Receipt

at the last sitting which was

the 24 of this present Julie 5015 lbs 06 d

all yssues being made which

then were ordered did amount

vnto

Paymentes ordered at this sitting

Master Phillipp Maynewering Cupbearer 91

to his Majestie

Master Mynn Knight Harbinger 13

Archibald Rankyn servant to the Prince 12

John Leslie Master Cooke to the Prince 14

John Seringis the Queens Chaplen 40

Thomas Morton waymaker 20

The lady Bartlett 20

The kinges Tailor 30

Seignior Biondi 100

Imprest for the commissioners of

the ??Navy?? 100

For finishing the lodge at Theboalds 50

Totall 490

Lett orders be presently made for

so many of these parcells as

require orders, & the rest

be presently paid.

Fulke Grevill

And so remaineth in the

Receipt cleere these issues

being deducted. 4525 lbs 6 d

_______________________

Bajetta, Carlo M, "Biondi, Sir Giovanni Francesco (1572–1644), diplomat and romance

writer," Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press,

2008) https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/2426

Barclay, Andrew, ‘Recovering Charles I’s Art Collection: Some Implications of the 1660 Act of

Indemnity and Oblivion’, Historical Research, 88.242 (2015), 629–49

Beauchamp, Peter, ‘The “servant” Extraordinary: Some Account of the Life of Thomas Beauchamp

(1623-c.1697), Clerk to the Trustees for the Sale of King Charles I’s Collections’, The British

Art Journal, 11.1 (2010), 6–18

Field, Jemma, ‘Anna of Denmark and the Politics of Religious Identity in Jacobean Scotland and

England, c.1592-1619’, Northern Studies, 50 (2019), 87–113

‘MAINWARING, Philip (c.1589-1661), of London | History of Parliament Online’

<https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1604-1629/member/mainwaring-philip-1589-1661> [accessed 7 March 2021]

Smith, Daniel Starza, Matthew Payne, and Melanie Marshall, ‘Rediscovering John Donne’s Catalogus

Librorum Satyricus’, The Review of English Studies, 69.290 (2018), 455–87

Unwin, George, Industrial Organization in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (At the Clarendon Press,

1904)

[1] Many thanks to Bradin Cormack for this transcription and his assistance in identifying the named individuals.

[2] For information on the tortuously complex process of settling the deceased king’s debts and selling his collections during the Commonwealth, then attempting to recover them after the Restoration, see the articles cited below by Peter Beauchamp and Andrew Barclay.It all begins with an idea. Maybe you want to launch a business. Maybe you want to turn a hobby into something more. Or maybe you have a creative project to share with the world. Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.